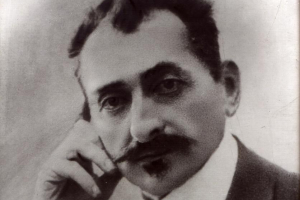

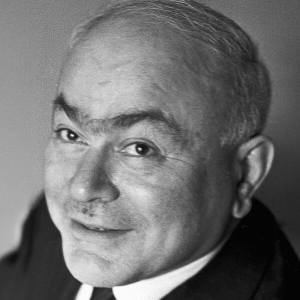

Niko

Sulkhanishvili

Niko Sulkhanishvili

(1871 – 1919)

Niko Sulkhanishvili – Georgian composer, ethnographer, lotbar, singer. The founder of Georgian professional choral music and the author of the first classical samples of this genre.

Date of birth – 1871

Place of birth – Atzuri village, Kakheti, Georgia

Date of death – December 3, 1919

Place of death – Tbilisi, Georgia

He is buried in Didube Pantheon of Writers and Public Figures – Tbilisi

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA

1878 – Receives his first musical education at Telavi Theological Seminary;

Since 1884 – Continues his studies at Tbilisi Theological Seminary;

1902 – At the Tbilisi Music School, he learns theoretical disciplines and takes private lessons in composition;

Later, he started studying singing with the famous teacher D. with Usatov;

1890–1900 – Teacher of singing at Telavi Theological Seminary

1900–1912 – Travels to Tbilisi and creates a group of Georgian singing lovers;

1886 – Creates the first choral works;

1912 – 1914 – With a folklore expedition, he starts recording folk songs in Kakheti;

1918 – Leads a paid team;

1919 – Head of the chapel at the “Georgian Philharmonic Society”;

Niko Sulkhanishvili

(1871 – 1919)

SELECTED WORKS

MUSIC FOR THE THEATER

1892 – “Little Kakhi” – (nickname of the King of Georgia Erekle II) – Opera in 4 Acts – Lost Score – Only Two Fragments Have Survived – Shepherd’s Aria “Late” and Patara Kakhi’s aria “I was hardly left alone”

VOCAL MUSIC

CHORUS A CAPPELLA

„Gutnuri“ („Song of the Plowman“) – (text – I. Chavchavadze)

“Homeland of Khevsurian” – for Solo Tenor and Mixed Choir – (text – S. Pashalishvili)

“Homeland of Khevsurian” – (text – R. Eristavi)

“Mestviruli” – (text – A. Tsereteli)

“Dideba Iversa” – for mixed choir

“Praise the name of the Lord” – for mixed choir

“God the Lord” – for three-part choir

“God the Lord” – for mixed chorus

“Great Querex” (“Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal”) – for three-part chorus

Lesser Querex

“So Victory Sweet Life” – for Soloist Tenors and Mixed Choir – (text – on a poem by S. Pashalishvili);

“God, God” – Hymn for Mixed Choir and Piano – (text – Sh. Rustaveli – Avtandili’s prayer)

Romance

“Mo, Zualo” – – for Voice and Piano

In Georgian music, the first turned to the poem by Sh. Rustaveli “The Knight in the Panter’s Skin”

Niko Sulkhanishvili

(1871 – 1919)

Niko Sulkhanishvili is a well-known representative of Georgia’s first generation of professional musicians.

Sulkhanishvili is widely recognized as one of the first presenters of the aesthetic principles of Georgia’s national liberation movement, “Tergdale people”. (Georgian intellectuals called “tergdaleulebi” (i.e. those, who have drunken the water of the Terek river) due to a clash of imperial Russian-Tsarist and feudal Georgian cultures on the migration from educational institutions from Georgia to St. Petersburg and back during the second half of the 19th century) in music. The “Tergdale people” regarded the revival of Georgian folklore, particularly musical sampling, as one method to enhance national identity. When Georgian folk music was in danger of being forgotten and, maybe, vanishing, Sulkhanishvili was among the first to not only keep its survival, but also create the foundation for its new vitality.

Throughout his life, Georgian song was his main theme. Folk songs have been a constant companion of suffering, illnesses, starvation and feast in his childhood environment, the village of Atskuri, in the corner of eastern Georgia, in Kakheti. Later, while studying at Telavi Theological Seminary, an original Georgian hymn keeps a special place in his soul. Later, in Tbilisi, as he gets to know with the repertoire of Georgia’s first ethnographic choir, the “Georgian Chorus,” Georgian musical folklore emerges in sight of him, revealing its wide range and richness. Niko Sulkhanishvili, together with Dimitri Arakishvili – the greatest promoter of Georgian folk music – travelled across the villages of Kakheti recording folk tunes, which later was performed with his own little choir. These events occurred prior to the creation of Sulkhanishvili’s original choral pieces based on traditional roots.

“Sulkhanishvili’s main historical value is that he created the basis of Georgian professional choral music by developing the first classical examples of this genre,” notes musicologist Vladimir Donadze.

Sulkhanishvili developed a cappella choirs, which are identical to folk tunes but lack instrumental backing. It should be emphasized that N. Sulkhanishvili expanded the realm of Georgian polyphonic singing by combining European choral composition with Georgian polyphonic thinking in his own unique way. Regarding to this context, the composer made samples of a mixed choir, which fused men’s and women’s voices.

It is also worth noting that he refused to use popular tunes, but instead developed his own style based on Georgian traditional regularities and established his own distinctive style. So, for example, he understood the old Georgian kilo-tonal system, of the parts of Eastern Georgia, and the kilos of alternation characteristic of Kartl-Kakheti – Mixolydian, Aeolian, Phrygian, Dorian – and based his choirs on them.

Unfortunately, N. Sulkhanishvili’s musical heritage has not been completely delivered to us. His legacy is minor but varied. Sulkhanishvili’s choirs differ in creative content, structure, dramaturgy, and sound. For example, the folklore heritage of Racha, a region of Western Georgia, is expanded in the choral piece “Mestviruli” (1913), which is based on Akaki Tsereteli’s poem “Chongurs Simibi Gaubi” ( Chonguri – four stringed lute), The resonances of the choir and the soloist on the folk instrument – Gudastviri (Bagpipe, musical wind instrument) – produce an imitation of harmony between the player and the people around him.

The timbral contrast of the mixed male-female choir produces a strong impression in the choral song “Samshoblo Khevsuri” (1913 by Rafiel Eristavi, poem.) The rhythm, tempo, and textural contrasts in this work are interesting. The key-tonal variations and placing this complex musical thread into a single compact shape are also significant. The chorus “Gutnuri” presented Georgian folk song as a harmonious development. (1913. Mix of “Gutnisdeda” by Ilia Chavchavadze). Through music, the composer emphasizes the existing images. The work clearly displays the plowing of the soil, led by the ploughman, as well as the participation of those around him peasants – in this process. That is why “Gutnuri” is his largest work. This piece is outstanding among Niko Sulkhanishvili’s choirs in every aspect. It is written for three soloists (tenor, viola, bass) and a four-voice choir, with a dialogic dependence of the soloist and choir, as well as different texture, timbral, meter-rhythmic register contrasts.

Today, it can be stated that “Gutnuri” finds an echo with the cantata genre and produces the basis for its creation in the new Georgian professional music because of its grandeur, depth of sound, composition, even an expression of epicness. With a strong attitude, powerful energy, and an optimistic mood, the choir “Mash, gamarjveba tkbilo sitsotskhlev” (Victory, sweet life), (1913 Siko Pashalishvili’s text), approaches Kartli-Kakhuri songs, and supruli (song traditionally sung at table). The author uses creative principles common to extended tableaus, especially “chakrulo,” the most essential of which is the singing of soloists on a variety of chordal backgrounds sung by bass voices. The relationship between the soloists and the chorus, like in “Chakrulo,” is depicted here with a rich, immense harmonic-polyphonic structure.

The chorus is entirely different – in the chorale “Gmerto-Gmerto” (Oh God), (similar to a passage from Shota Rustaveli’s poem “Vephkhistkaosni” (The Knight in the Panther’s Skin)). The author rejects the dramatic concepts and contrasts that characterized his previous works in this piece. The song “Gmerto-Gmerto” is inspired by Christian hymnography. The work’s extensive religious attitude and anthemic tone, as well as the intonation development and common texture typical of Georgian hymns, lend to this impression. This choir is also notable for combining the ideas of folk key-tonal and classical major-minor systems.

Sulkhanishvili created a number of unique techniques based on Georgian folklore. According to composer Nodar Mamisashvili – “Sulkhanishvili is the author of an innovative method in composition – the entire variety of modal motifs, which implies the horizontal arrangement of the melody as a series of “mosaic” modes of small motifs”. This concept inspires types of double improvisation in his choirs.

Georgian poetry was a source of inspiration for Sulkhanishvili. According to the works that have reached us, he put great value on the artistic worth of literary works, that’s why he regarded the works of Shota Rustaveli, Ilia Chavchavadze, Akaki Tsereteli, and Rafiel Eristavi.

Patriotism is a major element in Niko Sulkhanishvili’s artistic world. This theme influences his choral work, as shown by the pieces “Motherland of Khevsuri”, “Mestviruli”, and “Dideba Ivers”. It is worth noting that the composer chose a piece created on a patriotic topic for his opera, and he used Akaki Tsereteli’s patriotic drama “Patara Kakhi” for this purpose.

This opera had a sad and mysterious ending, as after the composer’s death, manuscripts were lost. Only two of them reached us: The opera episode: Kvabulidze’s aria – the song “Daigvianes” (They were Late) and Patara Kakhi’s aria “Hardly left alone”, both of them leaves a powerful impression on the listener.

On the one hand, Niko Sulkhanishvili kept on the legacy of unique Georgian folk choral music, and on the other, he established a new direction for its development. Despite having a little legacy, the composer had a significant role in Georgian compositional art.

Musicologist

Tamar Tsulukidze

English Language Translator

Tamar Kharadze